-

Introduction

The native Brazilian people are portrayed as inhabitants of places such as closed forests with the use of paintings, dances, rituals, enchantments as a form of expression of their art and emotions and their own ways of living and understanding the world and nature, which is totally different from the enslaved black communities, In other words, the black population in Brazil has in its history marks of resistance, oppression, and violence imposed by hundreds of years of compulsory slavery in the country.

To this end, the research focuses on history, memory and identity in the pottery production of quilombola women from Itamatatiua (located in Alcantara, Maranhão State), based on strong documentary evidence of indigenous influence in the production process, decolonizing the assumption consolidated until the knowledge about the mentioned production was passed on by the friars of the Carmelite Order, who owned farms and potteries in the locality, between the 18th and 19th centuries.

Thus, it is in this context, surrounded by stories and memories linked to slavery and resistance, that the Itamatatiua remnant community is found. It is one of the oldest in the state, due to this socio-environmental characteristic of its territory, using this slope to study the symbolic discourses of the black and quilombola history, besides presenting the dynamism over the centuries of its community; the perspective of an increase in tourism focused on experience and experiences.

Therefore, it is said that this research brings with it the approach of the different historical and cultural processes of the quilombola community and the original peoples and the cultural contacts that resulted in the ways of making ceramics. The quilombola regions, forgotten and undervalued by most of the Brazilian population and public policies, are unfortunately still known in a pejorative way (as "land of black people or mocambos"), even though they are officially institutionalized spaces of collective memory, cultural identity, and ancestry; and, one cannot forget that they remit the bonds of affection and belonging for their original community and also for those who know them and share their experiences, knowledge, customs, and beliefs with them.

-

Method

In this research, due to the highlights of ancestry and secular ceramic production, we chose to listen to the extraordinary storytellers who synchronized their memories with the manual skills when carving their ceramic dishes, i.e., the documentary bases are complemented with stories full of rich narratives. Therefore, this article reflects the systematization of data from the documental research, based on ethnography, in order to offer other readings for the understanding of the genesis of pottery in Itamatatiua, from a diachronic and synchronic point of view. For this purpose, different sources were gathered, such as historical documents, oral narratives, ethnographic descriptions and archeological evidence.

Furthermore, for the diachronic understanding of the trajectory of this craft, it is essential to build new problematics, to seek other sources of data, and to project interdisciplinary approaches, such as historical research, oral narratives, linguistics, ethnographies, and archeological investigations. Therefore, the scanning and reconnaissance inventory method was applied, a valuable tool for characterizing the historical and cultural assets of a given region, relating to a specific category or a particular theme (BANDEIRA, 2018).

Considering the ethnographic slope of the observation carried out, we start from the premise that the ethnographic method consists of a dense and descriptive analysis of the context in which the researcher is inserted, where:

[...] doing ethnography is like trying to read (in the sense of 'constructing a reading of') an awkward, faded manuscript, full of ellipses, inconsistencies, suspicious emendations and biased comments, written not with the conventional signs of sound, but with transient examples of modeled behavior (GEERTZ, 1989, p. 20).

Furthermore, considering that the Federal Constitution of the Brazilian Federative Republic provides for the protection of both material and immaterial heritage (art. 216), motivated by the Quilombo of Itamatatiua also bring the inclusion of cultural manifestations representative of peoples forming Brazil (indigenous ethnicities, quilombola groups, traditional communities and popular classes), therefore, it is clear the understanding that, this heritage has to be richly studied to apprehend how the memory of a craft, ancestry, identity of the quilombolas is relevant to the history of Maranhão.

-

Results and Discussions

In this work, we opted for a collaborative and participatory approach with the women potters through participant observation of the ways of making and designing the ceramic artifact, its social use, reuse and disposal, using an "archaeological ethnography" of artifacts (BANDEIRA, 2018).

In the face of this research, as specific results, we reached the understanding that the inventory of an ancestral way of making goes through the understanding and the active and collaborative involvement of the community involved with it is cultural references. In this way, the subjects of the different social and cultural contexts play a role not only as informants, but also as interpreters and actors of their historical and cultural assets. Thus, in addition to scientific and academic aspects, the knowledge generated by the inventories is extremely important for providing subsidies for the elaboration of cultural policies to safeguard, protect, and disseminate cultural assets, as well as for the strengthening and political autonomy of the collectives.

-

The Quilombo of Itamatatiua: memory, territory and territorialities

The Quilombola Community of Itamatatiua is one of the largest settlements in the rural area of the Alcântara municipality, located in the coastal portion of the Maranhão Amazon, on the limits between the Golfão Maranhense, Cumã Bay and the Reentrâncias Maranhenses. This traditional territory is also on the border of two of the most important preservation areas in Maranhão: the Reentrâncias Maranhenses and the Baixada Maranhense, also considered Ramsar sites.

The Ramsar sites in Maranhão make up the List of Wetlands of International Importance, an instrument adopted by the Ramsar Convention - an international treaty approved at a meeting held in the Iranian city of Ramsar - whose objective is to promote cooperation among countries in the conservation and rational use of wetlands in the world, in accordance with the recognition of their ecological importance, and their social, economic, cultural, scientific, and recreational values (ICMBIO, 2021).

In Itamatatiua, it is the transition from typical northeastern coastal-estuarine ecosystems into an Amazonian environment, where freshwater lakes abound in the region, bordering a coastline intersected by numerous streams that flow into the Golfão Maranhense and other points of the western coastal portion, called “Litoral de Rias”. In politico-administrative terms, Alcântara composes the Metropolitan Region of São Luís, for being about 30km away in a straight line from the capital, whose limits are only the Bacanga river mouth, the São Marcos Bay, and Boqueirão, on the Atlantic coast. IBGE (2020) data on the 2010 census attest that Alcântara has an estimated population of 21.652 inhabitants, however, projections for 2019 estimate a population around 22.097 people. The demographic density is 14.70 hab/km².

An important characteristic of the municipality is that it has a rural population exponentially larger than the urban population, with about 6.400 people living in the urban town center and 15.452 living in the rural area of the town. This equals 1.681 households located in the foundational nucleus, listed by IPHAN (National Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute) as a National Monument of Brazil, and 4.393 households spread over traditional territories, quilombolas, fishing villages, small towns and hamlets.

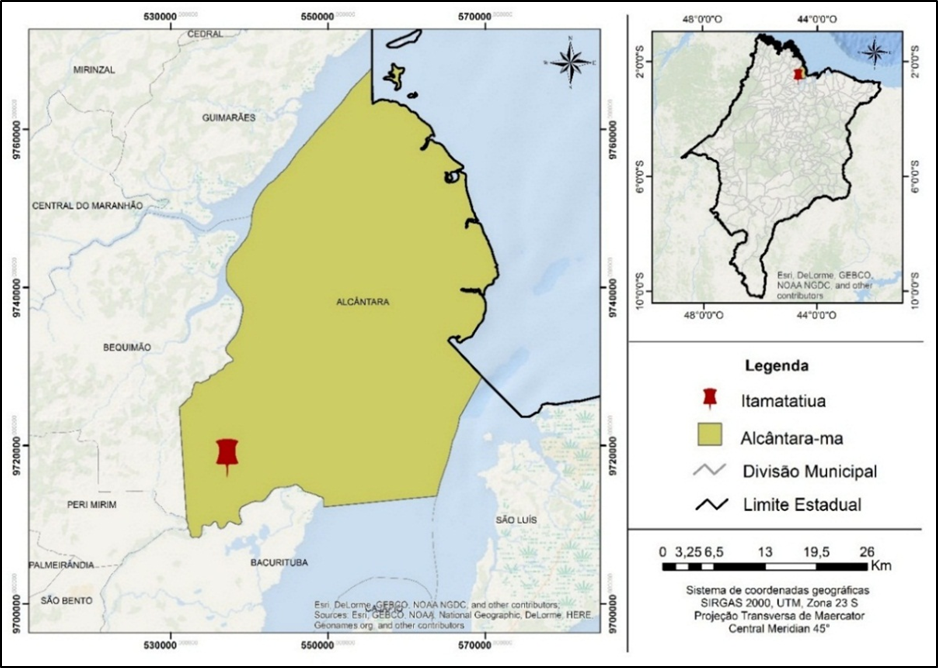

Itamatatiua is located in the northern part of the municipality, very close to the border with the municipalities of Bequimão, Peri Mirim, Palmeirândia and São Bento. In demographic terms, it has one of the largest quilombola populations in the municipality, and is also one of the most distant from the main town. The population data are not precise, but according to oral information obtained in the Municipal Prefecture, there are currently about 145 families, which aggregate more than 450 inhabitants living in the village (the location of the Itamatatiua Quilombo is indicated in the map of Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Municipality of Alcântara - MA, with the indication of the Itamatatiua Quilombo. Source: authors, 2019

The date of the emergence of the Itamatatiua Quilombo is imprecise, since the historical data contrasts from oral accounts. The historical documentation informs that the origins of the village refer to the existence of enterprises of the Carmelite Order colonizing and indoctrinating in the region, mainly where the farms and potteries are, which after the decline of slavery were extinct and the remaining lands were left to the Afro-descendant population[2].

Well, the quilombos in Maranhão have been documented since the end of the 17th century. In Assunção's (1996) view, it was an endemic phenomenon of the slave society, especially after the massive introduction of slaves in the last decades of the 19th century. Already in the 19th century, its occurrence is abundantly registered in newspapers, in the correspondence of the military and police authorities, and of the presidents of the province (ASSUNÇÃO, 1996). Nevertheless, Araújo (1992) recognized that when studying the quilombos of Maranhão in a historical perspective, it was found that the information recovered comes only from those mocambos that were invaded, such as Limoeiro, São Benedito do Céu and São Sebastião.

Almeida (2016) recognized that the late abolition of slavery in Brazil allowed obtaining a type of information about quilombos that is practically impossible to access in other countries, such as autobiographies recorded in surveys, reports of escapes, imprisonment and daily life of the quilombos. However, no matter how diverse and numerous the documents about the Maranhenses quilombos, they do not offer a more precise idea of their social, cultural and daily way of life, restricting themselves to purely military aspects (ASSUNÇÃO, 1996). These records are grouped in the expedition commanders' reports; the records of captured quilombolas; in addition to other communications from the counties, terms and municipal chambers addressed to the presidents of the province, obviously reflecting the official discourse and the vision of the dominant colonizer.

In addition, the economic strength of Alcântara during the 18th and 19th centuries, the agro-pastoral activities based on the enslaved arm, the existence of a large population of Africans and their descendants living close to or on the properties and the sharp decline of farming at the end of the 19th century, are structuring factors that must be taken into account in order to understand the territorialization processes that took place in the region and the mechanisms involved in the quilombola villages.

Contemporary studies from a historical and cultural perspective date back to the 2000s, based on ideas and theories on the protection of historical and cultural heritage, with the need for safeguarding, belonging and action (SANT’ANNA, 2006). Therefore, this approach quickly echoed among researchers, communities and protection agencies, deconstructing some crystallized premises, in which cultural goods worthy of value are linked only to elites (once colonizer, European, white).

In the opposite direction, there was a growing interest in expanding the role of cultural heritage to include cultural manifestations that represent all the peoples that made up Brazil, especially indigenous ethnic groups, quilombola groups, traditional communities and popular classes. In Brazil, these themes only gained space, as noted above, with the promulgation of the Federal Constitution of 1988, in respect of the identity, memory and resistance of the different groups that formed Brazilian society.

Due to these new studies and particularity, Maranhão concentrated the largest number of certified quilombola communities in Brazil, going from six certified communities in 2004 to 816 communities in 2020, according to the certificates issued to the remaining quilombo communities (CRQs). The last of them was published by Ordinance No. 36/2020, published in the DOU of 02/21/2020, according to a consultation carried out at the Fundação Cultural Palmares (FCP, 2020). In the municipality of Alcântara, 157[3] Quilombola communities were certified according to a consultation by the same foundation (FCP, 2020).

As this is an area densely inhabited by remnant communities of quilombos, many studies have focused on the populations directly or indirectly affected in the region, especially at the time when negotiations for the implementation of the Alcântara Base began in the 1980’s[4]. The choice of the location for the construction of the Alcântara Launch Center resulted in serious social and cultural impacts on the communities that traditionally live in the region. In addition, the fact that these communities are remnants of peoples who experienced historical processes that bequeathed to the rural area of Alcântara different forms of territorialization, which bequeathed to contemporaneity a recognizably ethnic territory, such as the "Unique Territory of Alcântara", with about 78 thousand hectares and more than 200 remaining quilombo communities (INCRA, 2007)[5].

In this way, we will give particular attention to the secular practice that distinguishes the Quilombo from Itamatatiua, whatever it is, the ceramics.

4.1 The ceramist production in Itamatatiua

The pottery practice in Itamatatiua went through three stages. Production at the Carmelite pottery ended with the departure of the local religious order. Then, manufacturing took place in the artisans' houses, and, finally, production became collective, taking place in a workplace known today as the Itamatatiua Ceramic Production Center (CESTARI et al., 2014).

Pereira Junior (2011) also discussed the origins of the ceramist craft, speculating whether ceramic manufacture had existed since the presence of ancient pottery or whether even before the Carmelites had settled in the region, there were black quilombos's people who already mastered the technique, as officials documents already mention the Quilombolas of Itamatatiua. The oral memory of the residents always links the village with ceramics, especially construction.

Nevertheless, ceramic production remained after the domain of the religious and gained its own dynamic in the community. Large potteries were gradually replaced by small potteries, whose production units became familiar, designed to meet the demand of the locality and nearby villages. While utilitarian ceramics became manufacturing almost exclusively for women, made in backyards, when ceramists created the Association and got support for the construction of the production center, in 2005 (PEREIRA JUNIOR, 2009).

The shift from collective to family production influenced social and economic relations, gaining a dynamic of its own, such as the exchange of working days between women in the making of their pieces, not in the commercial sense, but in the associating that is so present among communities traditional (PEREIRA JUNIOR, 2011). Furthermore, the ceramist trade in Itamatatiua began with European religious people, who brought such work to blacks and indigenous peoples to supply roof tiles, tiles and bricks for the growing civil construction market in the Alcântara headquarters.

However, at the beginning of archaeological ethnography, another hypothesis arose about the origins of this craft (which proved to be feasible, including endorsed by a historical document discovered in the Overseas Historical Archive). It originated from an official letter dated September 1, 1769, in which the Governor of the Captaincy of Maranhão, Joaquim de Melo e Póvoas, forwards to the Secretary of State for Business of the Kingdom, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, indigenous pottery from the region of Alcântara, which had glazed with resin from jutaí, so that it could be analyzed.

In this context, the archaeological ethnographic data substantiated with the field research demonstrates the indigenous influence in the construction of ceramic knowledge in Itamatatiua, in addition, it is perceived in the nominations of some products, in technical gestures, in the forms and technology of preparation of vessels with the use of the roulette, accordion, spiral technique, which consists of superimposing the rollers (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure - 2 - Mrs Domingas de Jesus (Duduí) making her rolls. Photo: Bandeira, 2019. |

Figure - 3 - Rollers ready-to-use. Photo: Bandeira, 2019. |

Evidently, the contact with the European colonizer left strong marks in the ceramic making in Itamatatiua, especially in the burning processes in closed ovens that are observed in the Production Center, a fact that contrasts with the way of burning of indigenous peoples in Brazil, who traditionally use to open burning. However, one of the main characteristics of European utilitarian ceramics is the use of the lathe and this technique has never been incorporated into local ceramic making, even with some recent attempts.

-

Conclusion

As discussed, the benchmarks to understand the history of the Quilombo of Itamatatiua and its links with the ceramist practice, in most cases, linked this ancestral knowledge, which now in decolonial understanding, is known to have had, in addition to the quilombola influence, the European colonizer (and the Carmelite Order), he was also influenced by other formative cultural matrices, such as the indigenous one.

Throughout this article, it became clear that the emergence of ceramist production in Itamatatiua is complex, involving and going back to issues of memory, identity and ancestral practice that are the means and end of these activities. Nevertheless, it was necessary to seek other sources of information and methodological approaches, new possibilities in order to understand this social fact, based on cultural exchanges, exchanges, displacements and diffusions within the quilombola community of Itamatatiua, seeking to decolonize ideas and mentalities and creating new ones and rich ranges of research, focused on the history that communities themselves, most often forgotten and unattended, tell about themselves.